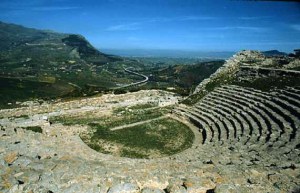

What is the role of comedy in the political life of a democracy? In Ancient Athens, comedy took place at festivals in which civic engagement was supported and the drama was penned with an entire audience in mind instead of an individual whereas American comedic appreciation takes place passively in front of the television or movie screen. The communal nature of Athenian theater also connected it to the democratic society, where citizens (albeit a minority of the population) were expected to engage in the public realm of politics and cultural life. Comedy was used as a tool to hold public citizens accountable, although not always fairly, as was apparent with Aristophanes’ portrayal of Socrates in his play “The Clouds.”

A sharp contrast with the Ancient Greeks, there is no special ritual surrounding American absorption of entertainment: no festivals, more an individual or small group immersion in leisure. What are the particulars of the gap between Greek theater and entertainment, so linked to a communal democratic society, and the American approach, as typified by television? In his essay, “Aristophanes in America” (available in part here) Euben lists voyeuristic, private, consumerist, passive, cosmetic, power-centric (although the “workings of power [are] invisible”), utopian, homogenous (catering to lowest common denominator), and ahistorical as qualities of the American television culture (107-8).

While television shows like The Simpsons, as Euben writes about, provide entertainment and an outlet of escape for Americans, they lack the “interrogatory role in our public life” to delve deep into the social conditions (116). While I agree with Euben’s evaluation of mass audience shows like The Simpsons or South Park, which may offer nuanced social commentary but will largely be taken purely for entertainment, to the right minds political satire like Jon Stewart’s Daily Show or the Colbert Report or certain other comedic outlets might not only spark an interest in political issues but also provide an engagement that could inform a wide public audience. Continue reading