Below is the edited version of an essay I wrote this year for a Philosophy of Film course at my college. The books cited are Thinking on Screen: Film As Philosophy by Thomas Wartenberg, New Philosophies of Film: Thinking Images by Robert Sinnerbrink, and the Deleuze-inspired Filmosophy by Daniel Frampton. Both offer some good perspective on the philosophy of film, albeit diverging in the fact that Wartenberg’s account takes a far more ananalytical approach, and his analysis of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind doesn’t make much sense (his chapter on The Matrix is spot on though). A few years ago, actually before I took classes on Aesthetics and Philosophy of Film from Prof. Paul Loeb, I considered movies and television to be purely within the realm of entertainment. While I’m still convinced that written texts are the best way for me to access and relay philosophical ideas, movies do offer an interesting, viscerally engaging means by which such ideas can be both probed through use of audiovisual effects, narrative plot, and objects within the film, sparking at the very least an interest, and at the most offering an argument and comprehensive exploration. Possibly the most interesting aspect of movies are their ability to capture ineffable elements of human experience language cannot describe, in a manner stripped of the phenomenological associations we generally have as the background of our direct experience, as Deleuze argues. Films are stripped down to the foreground, and in such a way provide an even purer sensory input than our real lives, though lacking integration with our senses of touch and smell.

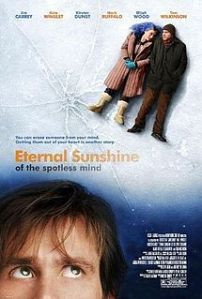

The Michel Gondry / Charlie Kaufman collaboration Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind provides a good example of the possibility of presenting philosophical concepts in a fictional feature film. This paper will show how Eternal Sunshine’s content supports ideas advanced by Wartenberg and Sinnerbrink that while films don’t explicitly present philosophical arguments as books do, they explore them in a unique way capturing the ineffability of human experience. Films are able to portray a fictionalized look at ostensibly real life while also given the ontological flexibility fictional narratives and special audiovisual effects and cinematic techniques provide and the detachment the viewer feels from the figments of the screen. Thus movies like Eternal Sunshine are philosophical both in the conceptual elements of their plot (in this case an exploration of memory and morality) and in the very nature of the viewer’s experience of a film: the medium’s ability to capture human experience in a way unlike any other, as Deleuze and Frampton argue. However, there are limits to the philosophicality of film: both in the content and the audience’s interaction with it. I will first explore the conceptual narrative aspect, and then the medium itself, before advancing criticism of my view, particularly Smith’s critique of the entertainment intent of the Hollywood movies like Eternal Sunshine.

Content

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a movie primarily about two lovers – Joel Barish and Clementine Kruczynski – who erase memories of each other using “targeted memory erasure” in order to forget their tumultuous romance. First the narrative is presented straightforwardly: Joel and Clementine meet on a train and strike up a romance. The story jumps to the characters’ past, in which they decided to undergo the lacunar memory erasure. The viewer is then transported into Joel’s mind, where the viewer sees Joel’s memories of Clementine and witnesses his struggle within his own mind to protect the memories as he’s realized his mistake in electing to partake in the procedure. The erasure would’ve succeeded were it not for a disgruntled employee of the memory erasure company sending out documents and tapes of erasure subjects to their homes. The unique aspect of this movie lies in the nonlinearity and the psychological aspects as we are brought inside Joel’s mind as he is objectively viewing his own memories. Eternal Sunshine belongs to a set of films pushing abstract boundaries of mainstream films, with nonconventional narrative structures and “ambiguous clues calling for indeterminate interpretation” (Sinnerbrink 153).

Through its philosophical underpinning, the conceptual backbone, the film portrays ideas by showing and not telling. Film as a medium is only inherently philosophical when viewed externally as a medium; it’s philosophicality rests otherwise in its content. Even if not, conceptual content is, pushing the reader into a dialectical relationship with the plot, as they interact with the happenings of the film and in turn are given a certain nuanced view of the conceptual underpinnings of the narrative. Eternal Sunshine in particular explores such philosophical areas of the philosophy of mind and memory, and concepts like free will. Not only does it prompt interesting ideas about the mind and memories enabled by the science fiction aspects (i.e. the lacunic amnesia memory loss treatment), but also the movie is a “counterexample to utilitarian moral philosophy,” as Wartenberg writes (93). The film at first seems to endorse the ethics of the memory erasure but ultimately by nature of plot progression, leaning towards a romantic optimism, and the devious intentions of various memory erasing workers (particularly Dr. Mierzwiak and Patrick) the moral intention of this miraculous procedure is called into question (Wartenberg 86). In a more abstract sense, the film also is an exploration of the idea of eternal recurrence presented by Nietzsche. As Joel and Clementine find themselves starting over their relationship together, we are left wondering if the process of memory creation and erasure will just repeat again, or if they will stray from their past as revealed through the memories of their former relationship. They fight against determinism and their past, renewing the audience’s hope in free will and romance.

Medium

I have explored the conceptual backbone that allows films like Eternal Sunshine to present philosophy, but what about the medium itself? Film as philosophy means not only a linking of concepts to film but film as its own means of thought interpretation, because films uniquely capture and portray feeling, as a “cousin of reality” (Frampton 1). Philosophy is able to explain certain stances, but film is able to show rather than say these philosophical positions (Sinnerbrink 133). Film is a language of its own, featuring particularly great “plasticity,” as the pictures and sounds take representational form and moreover have a degree of transparency in which the viewer can look through the representations at the identifiable objects themselves (Gaut 51). The cinema can be viewed as analogous with Plato’s Cave: the shadows as physical entities, we peer both at and through (Wartenberg 15). Logically, a language, even in an abstract sense, can advance a philosophical argument. I agree with Wartenberg’s moderate view that films are capable of doing philosophy to a certain extent (2). However, they are limited by how much they are tailored to their audience – entertainment vs. philosophical probing (Wartenberg 3). I also agree that films can not only illuminate philosophical theories but also “make arguments, provide counterexamples to philosophical claims, and put forward novel philosophical theories” (Wartenberg 9). However, as I will explore in my criticism of this view, there are limits to the philosophicality that depend on content and audience intention.

Film succeeds because of accessibility. They lead to “widespread” and “intense engagement” (Carroll 486). It shows the brain media mimicking experiences, capturing aspects of life indescribable by words in books, but still detached in part due to cinematic techniques. In particular, the technique of variable framing – bracketing, indexing, and scaling the picture to influence the viewer’s perception – leads to the technical aspect of movies allowing the viewer to easily interpret what is portrayed on screen (Carroll 490). Moving beyond the technical aspects of cinematography we can even look at a phenomenological dimension. Deleuze argues that film is so easily accessed, stripped of the phenomenological associations we encounter in real world experiences (Loeb Lecture 2/14/2013). According to Frampton, films aren’t a single or accurate reproduction of reality: they present a manipulative world of its own, a sort of daydream drug projected through thoughts of the real, explaining the viewer’s position in the world (2). Film can capture the concrete or particular of the world amongst other mediums (Loeb Lecture 2/14/2013). This is due to the fact that in real life experience humans have evolved to put up certain filters of their experience. Films, however, present raw visual and auditory sensory input while also maintaining the detachment of not presenting actual life experience for the viewer. Thus, films don’t assume a background ontology – we expect that background in real life experience but suspend it while watching films and just take in the film experience as sounds and images, not assuming a phenomenological depth. Thus, Deleuze thinks we can be closer to reality in film viewing mode then, assuming a different metaphysics (Loeb Lecture 2/14/2013). Film provides a certain purity of experience released from the pretensions of our individual realities – a grand unified perspective as each viewer is for the most part focusing on the same things, as the director directs them to, as opposed to the reader of a book who may be imagining certain aspects of what is described more than others, or not focusing at all.

The film medium’s accessibility isn’t limited to the audiovisual particulars and Deleuzian phenomenological simplicity: the emotional appeal of lifelike characters is also present. Movies with actors allow for a certain amount of character identification (Gaut 252). What distinguishes them from novels or other fictional narrative media which also foment emotional identification is the features like variable framing, which show the viewer exactly what to look at, and the accessible visual presence of the actors in the forefront. How does this lead back to the conceptual core explored earlier? Because of this accessibility and emotional appeal, movies attract the viewer’s attention and allow them to interact with the ideas brought to the fore. For the conceptual aspects of film to succeed there must be a degree of accessible interpretation, since the philosophical messages cannot be literally spelled out like in an essay.

By embracing a philosophical exploration giving the viewer the option of sorting out their own views on memory but ultimately endorsing a romantic free will idea as the viewer is left with the impression that Joel and Clementine will conquer their memory loss modification and revisit their romance, even though their relationship’s turbulence was the reason they had their memories of each other erased in the first place. While the movie doesn’t advance any specific philosophical thesis or agenda, it utilizes fictional films’ ability to probe human existence through the creativity allotted by the very nature of film making and its ability to capture the contours of human existence indescribable in words and channel them into an extremely accessible medium that mimics human experience with sound and moving images that doesn’t pretend to supplant actual existence for the viewer, as they know they are only watching a film.

Criticism

The idea of films presenting philosophy is certainly not universal. Though he doesn’t believe movies’ epistemic and artistic values to be “mutually exclusive,” Smith believes that entertainment takes precedence over philosophy in films (39). A specific condition for philosophy in his eyes is the explicit advancement of an argument. Smith argues that the narrative is not “literally speaking” an argument (34). Wartenberg dismisses this explicitness objection to film as philosophy as being faulty; since ambiguity isn’t merely confined to the realm of art and can also be present in philosophical writing – dependent upon the content and the interpreter (17). However, bridging off of this, one can make the case that the accessibility and entertainment allure of films will prevent viewers from focusing on the conceptual or philosophical statements in the film. They’ll be so distracted by aesthetic sensation and the very flashy, viscerally engrossing nature of popular movies to even realize the deeper conceptual background, if it is even present.

The film medium, at least as it is typically used for mass media entertainment, is limited in its ability for it to explicitly present philosophical theories and for the audience to interact meaningfully with the plot in order to reach conclusions about the philosophical ideas presented, without either not actively participating enough or even realizing the philosophicality of the film due to the entertainment factor. The simple problem is that films are by and large tools of entertainments; whereas when the average viewer watching even a more cerebral film like Eternal Sunshine will likely mostly focus on the movie for entertainment purposes, i.e. passively, they certainly wouldn’t think the same about a book written by a philosopher. Very few laypeople read Kant or Deleuze for fun. But therein also lies what makes film so special. Its immense reach and accessibility at least ideally triggers some new thought in its viewers about the philosophical concepts it presents.

Conclusion

Eternal Sunshine could very well spark an interest in its viewers about moral philosophy or philosophy of mind, just as the teenager watching The Matrix may become introduced to Beaudrillard. Made impure (from a philosophical perspective) by the intent of entertainment, films also provide the popular appeal to introduce ideas to the populace, even if the philosophical concepts aren’t the primary focus or aren’t even realized by the majority of viewers. As a rebuttal to Smith and all the doubters of the philosophical potential of films, I believe that while film cannot replace philosophy as it is traditionally practiced, in the classroom or within the confines of textbooks, film offers a supplement a way to abstractly present philosophical issues in an accessible manner, sparking debate on the topics it explores without usually taking explicit positions or exploring the concepts outright. Rather, fictional movies like Eternal Sunshine use their plot creativity and the innate elements of film to capture and portray human experience in a way philosophy can only theorize about, bringing these ideas to a very wide and diverse audience.

To understand the possibility of philosophy in film, the distorting hierarchy of philosophy and art must be abolished and they must be put on a similar level (Sinnerbrink 117). Instead of condescending to the mass audiovisual medium that has taken the world by storm like Smith or projecting philosophical thought from an external perspective like Mulhall, the middle ground advocated by Wartenberg and advanced in this paper presents the possibility to appreciate the entertainment aspects of films while also emphasizing the ability for film to espouse philosophical thought in its viewers. It would be prudent for philosophers to take note of this powerful medium and utilize it to revive dwindling interest and understanding of academic philosophy: not as a replacement for books or professors, but a spark for interest in concepts and an understanding of how they can materialize in ostensibly real world situations, which can be viewed with the detachment of a viewer who knows they are fictional and doesn’t confuse them with their particular phenomenological reality but more as a collective “daydream drug” illusion.